Introduction

This unit focuses primarily on how to create diverse opportunities for students at the JSS level to develop their English language skills through exposure to the language of literature. This will involve engaging students with various genres of literature such as poetry, fiction and drama to develop their vocabulary and mastery of grammatical structures. The unit also aims to help you introduce to your students the different stylistic forms of literary texts. The objective of this unit is to enhance language use through familiarity with a range of vocabulary and structures as used in literary texts. This approach to the study of literary texts, leading to language-literature integration, sees literature classes as laboratories or practical workshops for the development of students’ language and communicative competence.

Unit outcomes

Upon completion of this unit you will be able to:

|

Outcomes |

|

Terminology

|

Terminology |

Discourse patterns: |

Text arrangements beyond the sentence level, including paragraphs, connectors, etc. |

Genres: |

Types of literature such as poetry, drama and prose. |

|

Language competence: |

Language proficiency that includes the ability to communicate effectively in a language. |

|

Communication skills: |

The ability to use the language skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing to effectively perform various language functions such as greeting, agreeing, requesting, exchanging social niceties and so on. |

|

Communicative competence: |

The ability of speakers of a language to know what to say to whom, and when. In other words, communicative competence includes the knowledge of the vocabulary and structures of the language as well as the social norms of speaking. |

|

Integrated approach: |

This suggests using literature to teach language skills and the resources of language (words, collocations, sentence structures, paragraph connectors, metaphorical expressions, etc.) to teach literature. |

|

Literacy skills: |

These include the ability to read and write in a language. |

|

Critical thinking: |

This involves the ability to reflect on a piece of spoken or written discourse (of at least one paragraph) and to evaluate its strengths and weaknesses in terms of both conceptual and language clarity. |

Teacher support information

The aim of this unit is to use strategies and resources to enhance the language competence of your students through literature. In this unit, you will be able to use your familiarity with the literary devices used in prose, poetry and drama to help your students to communicate more effectively and eloquently. You will also find ideas to encourage your students to explore the interesting uses of words, phrases and sounds in literary texts. This should increase students’ awareness of literary language and help them understand literature better.

Case study

|

Case study |

In Mr David Ilemede’s English class at Demonstration Secondary, students worked on a play called The Wives’ Revolt by J.P. Clark. As part of the project, the students were asked to focus on different aspects of language demonstrated in the play. The students began by reading and acting out excerpts from the play with their teacher. For the performance, they were encouraged to choose the sections that they found most interesting. Mr Ilemede followed up on this enjoyable experience by encouraging the students to look more carefully at the sections they had chosen, to see how the grammatical structures of the sentences and word groups made the play more interesting. Working in groups, the students selected sentences, nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs and their combinations in phrases and clauses. With Mr Ilemede’s help, they began to identify the special meanings that these combinations of literary expressions brought to the play. After this activity, Mr Ilemede prompted the groups to use the interesting structures in their own stories. They were encouraged to illustrate their stories with pictures, charts, diagrams and drawings. The students greatly enjoyed this experience as it gave them an opportunity to use grammar in interesting and creative ways. They were also happy to see how the same language resources (sentences, clauses, phrases and word combinations) could be used in interesting ways in different literary genres such as plays and stories. |

|

Points to ponder |

|

Activities

Activity 1: Using poetry to develop vocabulary in context

|

Activity 1 |

In this activity students work collaboratively to familiarise themselves with expressions specific to poetry, and to see how these create interesting meanings in English. Divide the students into five or more groups and give them a variety of short poems to read. Ask each group to identify at least one expression (a word or a group of words) in the poem that they think is used in an interesting or unusual manner. Let them come up with their own explanation of why they think the expression(s) is (are) special. If you can, put the expressions you collect from each group on the board and have a class discussion about them. You can use this as an opportunity to highlight the literary use of language in poetry, such as rhyme schemes, figures of speech, alliteration, personification, similes, metaphors, etc. During the discussion, ask the students in their groups to try to rewrite the poetic expressions in “simple” or “normal” English. For example, in this line from Longfellow’s poem “Rainy Day”: My thoughts still cling to the mouldering Past there are at least three unusual uses of language: thoughts… cling… mouldering Past, and the word mouldering itself. If we try to make these expressions “normal” or “everyday,” we will realise that thoughts cannot cling; they can come/go/focus on. We can use adjectives like remote/long forgotten to refer to the past, but the expression mouldering is unlikely to be used. In fact, mouldering is not listed in the dictionary (although to moulder is). It is an unusual coinage, perhaps stemming from the word moulding which suggests “something becoming bad from misuse.”

The function of these two games is to teach students the value of interpreting the special meaning(s) of a poem by focusing on its vocabulary. Students will also realise that a group reading of poetry can be a very enjoyable experience, and that one can interpret the same poem in different ways by guessing at different meanings of the vocabulary in the poem. After the exercises are done, you could read the poem aloud or play the audio and have the class give a choral reading of the poem after listening to it. This would not only improve their recitation skills, it would also personalise the poetry reading and help them understand it better. |

Activity 2: Developing creativity in language use: Converting a prose text to a play

|

Activity 2 |

In this activity, students work in groups of five to convert a short piece of prose (preferably a story of one or two pages) into a play after they have read and discussed the story.

This activity offers students strategies and opportunities to read, plan, outline and rewrite stories, and listen to play rehearsals and videotape their plays. As they carry out these tasks, they have the opportunity to listen to, speak, read, write and proofread language used in at least two different contexts. |

Activity 3: Creativity in collaboration: Using students’ language resources for story development

|

Activity 3 |

At the JSS level, students are usually asked to compose short stories from a given outline. While such classroom activities help them practise the skills of composition by recreating a storyline, they do not encourage them to exercise their creative abilities. Creative composition skills involve the ability to develop a storyline by weaving ideas together in an interesting and logical sequence. The activity given here is meant to encourage students to express themselves creatively through a fun-filled group task. It is also meant to give them training in thinking logically and connecting ideas to develop a composition in an interesting way. To prepare them for this story-development task, give them a homework assignment a day before. Give them two versions of a short story to read. The first version should contain the original story and should have a clearly developed storyline, with well-developed characters and a narrative that progresses logically with a beginning, middle and end. The second version should have some distortions in style, such as an unclear storyline, no clear progression from beginning to end and hazily sketched characters. The students’ task is to individually mark which story is “better” and more interesting to read, and why (i.e., what differences are there in the two versions). The objective of this homework task is to help them find out for themselves the important ingredients of a good story so that they can use this knowledge for their group storytelling exercise. For the actual exercise, have the students give a report on their homework assignment. You could list the points they give on a board. The preliminary discussion should cover the features of a good story, like the ones listed in Resource 2 for Activity 2 above. Organise the students for the storytelling task in the manner suggested in Resource 3. If possible, videotape the storytelling task, and play it back to give the students a chance to refine their own lines and make them more interesting, crisp and creative. |

Unit summary

|

Summary |

In this unit, you learned how to help students develop their language competence through exposure to various samples of literature. You learned about the need to listen to and orally practise story and poetic presentations, and about the need to expose children to creative writing for a variety of purposes and in a variety of settings. |

Reflections

|

Reflection |

|

Assessment

|

Assessment |

|

Resources

Resource 1: Using a poem for vocabulary enhancement

|

Resource 1 |

To play this game, divide the class into two groups. The first group will have words and phrases related to the poem “The Improbable,” and the second will have the matching meanings. Begin the game by asking a member of Group 1 to raise a flashcard with a word or phrase on it. Group 2 now has to raise the flashcard with the matching meaning. For example: Student A (in Group 1 raising the flashcard): Which expression in the poem means “unlikely”? Student B (in Group 2 raising the flashcard): “Improbable” Note: If you think your students will find this task difficult, you can modify the question by mentioning the stanza number. This game continues until all the questions in column 1 have been asked by Group 1 and answered by Group 2.

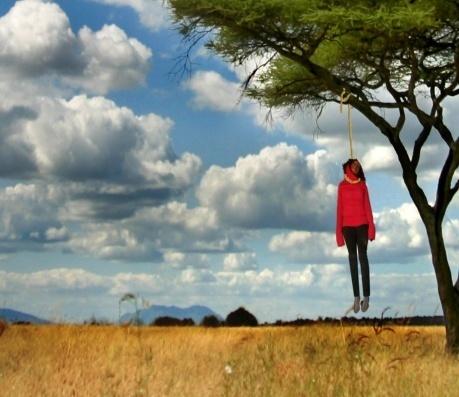

“The Improbable”

The improbable happens in unexpected places- A young woman of twenty three hangs herself After leaving a note: “Nobody loves me, I have no man” What a pity, what a pity, what a pity.

None would have thought it possible That a nubile woman would die for lack of love When too many were dying for making love- And many sell love in public places all over the world

The new disease afflicts so many who love in haste The disease is not written on the face and knows no bound They have searched in vain to cure themselves of love Love that’s a scary scourge in the eyes of the wary.

And yet who’s spared from debility and death That love proffers to lovers tied her a noose Her favorite wrapper to a fruiting tree outside Love that is not in haste is not in waste. |

|

Audio |

Resource file http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjbzhF8JNF4 See in the enclosed DVD an audio recording of the activity:

|

Resource 2: Guide to editing

|

Resource 2 |

The following checklist can be used to evaluate a piece of prose fiction (i.e., a story):

(See the sample short passage developed in Resource 4 below) |

Resource 3: How to organise circular storytelling

|

Resource 3 |

Circular storytelling is a good way to unlock the imagination and develop listening and reasoning skills in a creative and entertaining way. To organise the circular storytelling:

|

Resource 4: Guide to summarising a prose text

|

Resource 4 |

The prose text below is used to illustrate how you can summarise a prose passage.

There were mosquitoes everywhere when the rain came. John found some in his shoe. Emily saw three on the cooking pot and their father found several in his car. The whole village was infested with mosquitoes. This situation made the whole village call a meeting. They had a debate. How would they get rid of the mosquitoes? Every person got a chance to speak, and everyone listened carefully. The people discussed each of the suggestions made by both the wise and the foolish. However, none of the ideas was good enough. Then, an old woman who was sitting at the edge of the group, put up her hand. She told the villagers that in a small bush far away near Benue River, there was a plant with anti-mosquito odour. It was a magic herb. When it was burnt, the smell attracted all mosquitoes to the fire. The people decided that this was an excellent idea so they sent three people to get the plant.

Mosquitoes everywhere/whole village infested/issue worrisome/ discussion of the issue/old woman’s suggestion/plant in a bush near Benue River/attracts mosquitoes/three people sent to get the plant.

During the rainy season, mosquitoes infested the village, creating a worrisome situation that needed to be solved. The villagers accepted the suggestion of an old woman to use a plant near Benue River that could attract all mosquitoes and destroy them. |

Teacher question and answer

|

Feedback |

Question: What happens in a class where about half of the students cannot read or write English well? Answer: In such a situation, do not ask a student who is not confident about using English to perform all the activities in this unit. Give the students comics written in good English to begin with. They can then start reading stories meant for younger children, moving up gradually to literature appropriate to their level. |

|

|